SEVIS 2019: Language training, associate degrees, and considerations of distortion (part one)

Photo by Pawel Czerwinski on Unsplash

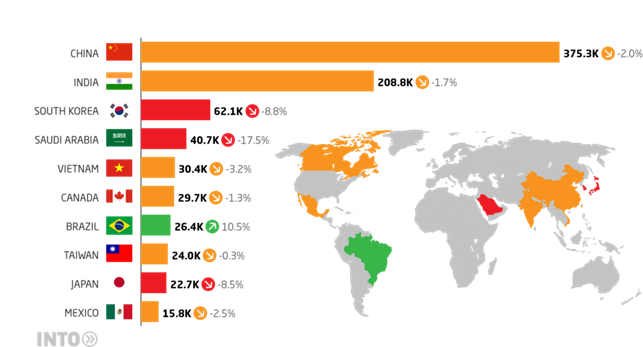

The United States Department of Homeland Security recently released quarterly data from the Student and Exchange Visitor Information System (SEVIS) that revealed a 3.1% drop in the number of foreign students in the US—the difference between 1.21 million in December 2017 to 1.17 million in December 2018—sparking widespread concern throughout the international education field. The data confirms that nine of the 10 countries that send the highest volumes of international students to the US registered fewer numbers of student visa-holders in 2018 than they did in 2017. Additionally, it shows drops in all but six states’ share of the total international student population.

Following the first wave of responses to the latest SEVIS release, many of which cite evidence of a near terminal decline in the number of international students choosing to study in the United States, it is important to consider how some trends impact on general international enrollment declines more than others. In this first post of INTO’s two-part SEVIS data analysis, we demonstrate how one underlying trend in particular—the decrease in the number of language training and associate degree-seeking students coming to the US, amplified as it is by long-term declines from source markets like Saudi Arabia—exaggerates the decrease in the total number of international students recorded by SEVIS, masking growth at other levels of study and distorting the latest snapshot of international enrollments in the US.

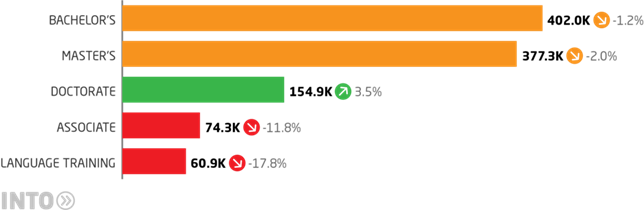

Source: SEVIS data December 2017 – December 2018

Source: SEVIS data 2014 – 2018

Language training and associate degree enrollment declines depress overall international student numbers in the US.

Of the many trends captured in the latest SEVIS data, significant decreases in the number of language training and associate degree-seeking students, combined with long-term declines from source markets like Saudi Arabia, contribute to disproportionate decreases in the international student populations of some states and mask growth in international student enrollment at other levels of study, skewing the profile of all international enrollments in the US.

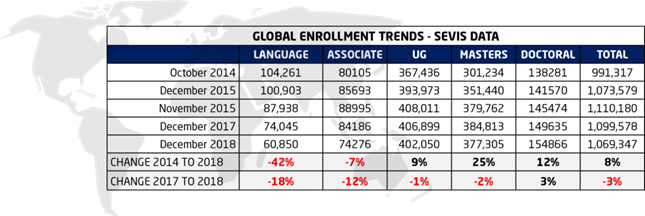

Drops in the number of language training students across nine of the US’s top 10 international student source markets culminated in an 18% decrease in the number of language training-seekers last year, from 74,405 in 2017 to 60,850 in 2018. This fall constitutes the latest chapter in a four-year period of decline for the number of international students who pursue language training in the US. From October 2014 to December 2018, international enrollments at this level of study in the US dropped by 42%, from 104,261 to 60,850. Put differently, students in language programs accounted for 11% of the total international student population in the US in fall 2014. In 2018, they accounted for just 6% of that total.

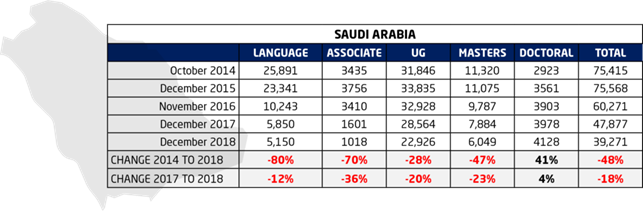

Source: SEVIS data 2014 – 2018

Saudi Arabia’s impact on these numbers is particularly startling. Over the same period, the number of Saudi Arabian students studying English language programs dropped by 80%, from 25,981 to 5,150. As a result of this decline, Saudi Arabian students constituted 25% of all language enrollments in the US in October 2014 but, by December 2018, accounted for less than 9% of those enrollments.

Source: SEVIS data 2014 – 2018

Meanwhile, the number of students seeking associate degrees in the US fell by 12% last year, from 84,186 in 2017 to 74,276 in 2018, following a period of sustained growth between 2014 and 2016. These declines are significantly more dramatic than those witnessed in the number of international students who pursued bachelor’s and master’s degrees in the US last year—at which levels of study there was a 1.4% and a 2.3% drop, respectively. They also mask growth—albeit small—of 2.8% in the number of international doctoral students in the US in 2018. Excluding the declines in the number of language training and associate degree students coming to the US, which accounted for more than 23,000 of the total decrease of 30,000 in the international student body in 2018, the general decline between December 2017 and December 2018 shrinks from 3.1% to 0.8%.

In the context of the last four years, decreases in the number of international students pursuing language training and associate degrees are the only consistent drivers of overall decline in international enrollments in the US. Despite marginal dips in the volumes of international students coming to the US for undergraduate and master’s-level study in 2018, the numbers of international students enrolled at these levels have grown by 9% and 25% since 2014, respectively. Combined with 12% growth in the number of international doctoral students in the US between 2014 and 2018, increases in the volumes of international students at these levels of study outweigh declines in the populations of those pursuing language training and associate degrees and contribute to 8% growth in the total number of international students in the US between 2014 and 2018. In fact, taken outside of the context of language study and associate degree declines, the total student population would have grown by 11% during the same period.

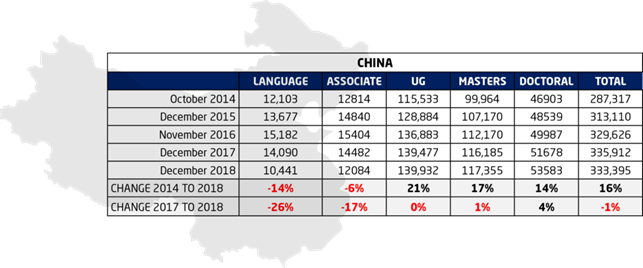

China: How decreases in language training and associate degree students contributed to the first declines in a decade.

While the number of Chinese students in the US declined for the first time in a decade last year—a 2% drop overall—the Chinese student population has still grown by 16% over the last four years, from 287,317 in 2014 to 333,395 in 2018. Once again, decreases in the number of language study and associate degree students—26% and 17% drops, respectively, in China’s case—bear disproportionately on declines coming from top source countries at the same time as enrollments at other levels of study remain stable or continue to grow. A 26% drop in Chinese language training students and a 17% drop in Chinese associate degree-seekers in the US in 2018 distorts the stability of the numbers of Chinese students pursuing all other levels of study. There was virtually no change in the number of Chinese students choosing to complete undergraduate study in the US in 2018, while the number of Chinese doctoral students grew by 4%.

Source: SEVIS data 2014 – 2018

Where China is concerned, one may well argue that a massive increase in the availability of English language instruction in country keeps more Chinese students at home, transferring to overseas study only after they have acquired basic language skills or taken advantage of the increasing amount of US high school and college preparation programs available closer to home. It may also reflect a drop in the number of the college-aged population in China.

Considering these significant declines, contained as they may be at certain levels of study, the question becomes: Are language study and associate degree trends the canaries in the coal mine? In other words, where the numbers of students at these levels of study have declined, will enrollments at other levels of study inevitably follow?

There is good reason to believe that this will not be the case for the biggest sender of international students to the US. On the other side of the Atlantic, the UK recorded its highest ever number of Chinese applicants for undergraduate study in 2018, even after declines in language training enrollments similar to those experienced in the US during the same period. Indeed, drop-offs in international enrollments have certainly not been the experience of INTO’s university partners in the US and UK, which continue to experience significant growth in Chinese student enrollments despite negative trends in language training and associate degree enrollments.

Demand for study in the United States from China remains strong. It may not continue to grow at the same rates as it has in previous years, and the shape of demand may well change. Nevertheless, trade wars and short-term political tension notwithstanding, there is no reason to expect that China will not remain the number one source country of international students for the United States for years to come.

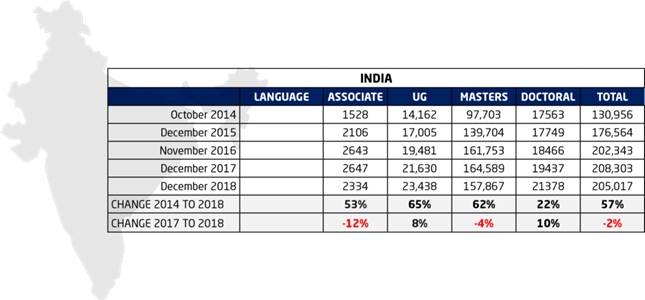

India: Beyond language training and associate degree student volumes

Of course, drops in language training and associate degree enrollments cannot explain every decline recorded by SEVIS last year. India, for instance, typically sends few students to the United States for language study. However, despite growing by 57%, from 130,956 in 2014 to 205,017 in 2018, the number of Indian students who choose the US as their study destination fell by 1.7% last year.

Rather than decreases in the number of Indian students interested in language study and associate degrees abroad, this decline is driven by a softening of growth in the number of students enrolled at the master’s level. After four years of explosive growth, the number of Indian master’s students has slowed down. This slow-down corresponds to an increase in the number of Indian graduate students choosing Canadian and Australian universities for their studies, due in no small measure to the increasing difficulty Indian students have gaining student visas in the US and well publicized concerns for the treatment and safety of Indian students in the US.

One positive trend buried within the SEVIS data, however, is the impressive growth in the number of Indian students choosing undergraduate study in the United States. With economic forecasts for India to overtake the United States and become the world’s second largest economy by 2030, and with a rapidly growing middle class, the increase in the number of undergraduate Indian students coming to the US will likely continue.

Source: SEVIS data 2014 – 2018

SEVIS: Meditations on distortion

Similarly to how a distorted guitar riff sounding in the middle of a Black Keys tune or the overuse of the visually distorting fish-eye lens in Yorgos Lanthimos’s The Favourite color their respective works with an unnerving quality, negative trends in the numbers of students choosing to pursue language training and associate degrees in the US have left some with the disconcerted notion that long-term declines in international enrollments are now inevitable. However, distortion, when understood for what it is, is not such a scary thing. While these negative trends complicate the whole picture of international enrollments in the US, they also demand that one look at the many instances of growth in international student volumes in 2018 and the last several years. The SEVIS release has posed challenges to higher education institutions in the US at the same time as it has presented them with opportunities.

In the second part of INTO’s SEVIS analysis, we further break down the ways in which these trends at the language training and associate degree levels, as well as long-term trends from top source countries like Saudi Arabia, have disproportionately impacted on the international student populations of certain states and institutions, as well as demonstrate the necessity of diversity in any international recruitment strategy.